Despite its rarity, it is important to recognize the risk of ASR in disseminated neoplastic disease due to its potential lethality. According to Orloff and Peksin, the criteria for the diagnosis of spontaneous splenic rupture include the following: (1) no history of trauma or unusual activity that could injure the spleen; (2) no evidence of disease in other organs that are known to affect the spleen and cause it to rupture; (3) no evidence of perisplenic adhesions or scarring of the spleen that suggests previously trauma or rupture; (4) if there are no findings of hemorrhage and rupture, the spleen is normal on both gross inspection and histological examination; (5) normal clotting studies; and (6) no elevations in viral antibody titers in acute or convalescent sera [3].

In the setting of advanced solid tumor malignancy, splenic rupture is most often linked to metastatic extension into the reticuloendothelial system, but limited literature exists to characterize this phenomenon. According to Lam et al., the two most common primary solid tumor lesions associated with spontaneous rupture of the spleen are metastatic choriocarcinoma and metastatic melanoma [4]. Overall, the incidence of ASR in the setting of secondary splenic tumors remains low. Lam et al. reported rupture in approximately 2% of patients in a study of 92 patients with splenic metastasis [4].

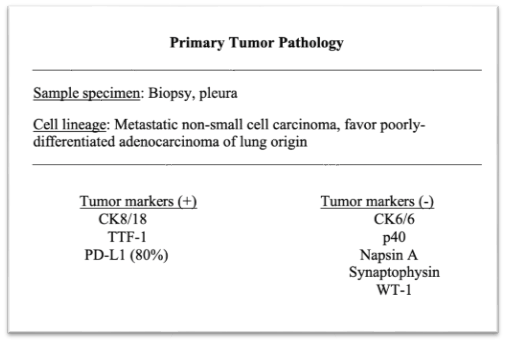

Current review of the literature reveals eight reported cases of splenic rupture occurring in the setting of metastatic lung cancer, as in our patient [1, 2, 5]. Ogu et al. and Massarweh et al. both describe cases of ASR secondary to metastatic NSCLC, depicting two different pathological mechanisms [5, 6]. Ogu et al. describes ASR with multiple foci of metastatic disease discovered on splenectomy with en bloc resection of the involved mesentery [5]. Massarweh et al. reports a case of ASR due to a solitary 10-cm metastatic lesion causing a large tear in the splenic capsule [6]. Both of the previously described cases depict gross pathological evidence of metastatic disease in the spleen. However, Kyriacou et al. described a case of ASR as the occult presentation of stage IV NSCLC, where there was no evidence of metastatic disease upon histologic examination of the ruptured spleen, as in our patient. To our knowledge, the current case report is only the second report in the literature describing spontaneous pathologic ASR in the setting of lung malignancy, without evidence of metastatic disease within the spleen itself. The underlying pathophysiology of ASR secondary to lung cancer, in the absence of splenic metastasis, chemotherapy, or G-CSF therapy, remains unclear [1].

The overall ASR-related mortality rate, irrespective of etiology or treatment modality, is 12.2% [2]. 21.4% of this mortality is attributable to neoplastic disorders [2]. Patients with ASR of malignant etiology should undergo immediate total splenectomy, although transcatheter arterial embolization may be used as a temporary stabilizing measure in some cases [2].

In conclusion, ASR secondary to metastatic NSCLC is a rare occurrence; though, failure to detect it may be fatal. Pathologic ASR may be an occult presentation of lung malignancy and in the presence of confirmed NSCLC may portend a poor prognosis. This case’s unique presentation highlights the importance of assessing splenic status in patients with disseminated NSCLC.